'The Visionary'

Born: 31st December 1864, Tuppers Plains, Ohio, USA

Died: 4th November 1945, Azusa, California, USA

George Willis Ritchey was not only one of the greatest designers of Telescope Optical Systems, but more importantly he was a visionary whose ideas were too radical for the age in which he lived. It was his collaboration with the French optician Henri Chretien that led to the optical design which now bears their name and which is the basis of almost all of today’s new breed of ‘super telescopes’.

On the 13th of December 1908 atop a mountain in southern California a ‘Great’ telescope opened its dome to see the night sky for the very first time. Not only was this a memorable occasion for those who had constructed it, but it also marked the end of one era in Astronomy and the beginning of another.

For three centuries ever since the days of Galileo the refracting telescope had dominated astronomical research in almost every observatory across the globe. Its rival the mirrored reflector was looked upon with scorn and contempt by the astronomical establishment. They saw it as the instrument of amateurs and cranks, and not fit to be given dome space in their Great Observatories.

Now the age of the glass lens and the refractor was gone, and the new age of the large silvered mirrored reflector had arrived; for the telescope that saw its firstlight in 1908, at the summit of Mount Wilson, over 5700 feet above sea level, was such an instrument. It had a mirror of 60-inches aperture, which at the time, made it the largest operational telescope in the world. The man who had ground, polished and nurtured the mirror was George Willis Ritchey (1864-1945).

He was born the son of a cabinet maker of Irish emigrant stock, in a small Ohio settlement whose name few have heard and not many more have lived in. Yet despite these humble beginnings and probably because of them, he grew up to become not only a great optician and telescope designer, but also an outstanding Astrophotographer whose images of Deep Space Objects (DSOs) were the finest of their day

His images of such iconic objects as the as Great Spiral Galaxies in Andromeda (M31),Canes Venatici (M51), Ursa Major (M101) and Triangulum (M33) were of the most incredible quality and greatly improved upon those taken earlier by the likes of Andrew Ainslie Common, Isaac Robert, James Edward Keeler and William Edward Wilson.

In 1910 in collaboration with the French optician, Henri Chretien (1879-1956) they designed the now famous Ritchey-Chretien optical system affectionately known as the RC. It was this design that brought George Willis Ritchey and the Mount Wilson Observatory’s Director, George Ellery Hale into conflict. Ritchey believed he should at least have been allowed to make a prototype of the new design, but Hale was adamant it was too new and too different to waste precious time on. Any telescope he had anything to do with would be constructed using traditional designs only.

In 1919 Hale fired Ritchey, but not before he had finished work on the mirror for his new 100-inch Hooker reflector. A deeply hurt and disillusioned Ritchey left the mountain, never to return. Left to ponder what might have been, he scratched a living growing oranges, lemons and avocados.

In 1928 Ritchey wrote of his dreams for the future of telescope design]:

“This is the incomparable exploration - the effort to bring the resources of the Universe to the service of mankind. This series of telescopes, by revealing to all men, graphically, by means of exquisite photographs, a Universe of which the Earth, the Sun and the Milky Way are but an infinitesimal part, will bring to the world a greater Renaissance, a better Reformation, a broader science, a more inspiring education, a nobler civilization. This is the Great Adventure. These telescopes will reveal such mysteries and such riches of the Universe as it has not entered the heart of man to conceive. The heavens will declare anew the Glory of God.”

On the 24th of April 1990 an event took place which proved Ritchey right and Hale wrong. The words spoken by George Willis Ritchey over sixty years earlier, eloquently described the work that the Hubble Space Telescope launched that day was soon to perform, but especially so - as it was his optical and Chretien’s design which made it all possible.

Ritchey and Chretien were visionaries ahead of their time, often vilified and ignored by the astronomical establishment for their ‘new curves’ optical design. Today in space and in an ever increasing number of backyards and gardens across the world these two men’s names are remembered for the ‘new breed’ of telescope that has changed and is still changing our understanding of the universe in which we live.

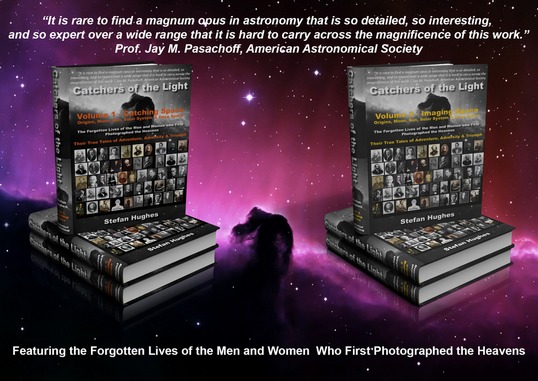

To read more on his life and work read the eBook chapter on George Willis Ritchey or buy the eBook 'Catchers of the Light'.

'Edge On' Spiral Galaxy NGC 4565 in Coma Berenices, George Willis Ritchey, 60-inch reflector, 1910: Photograph courtesy of Mount Wilson Observatory

Buy the eBook or Printed Book at the 'Catchers of the Light' shop.